Depending upon which research you choose to believe, ‘High-Potentials’ amount to anywhere from 2% to 15% of an organisations’ employees.

There are countless books, articles, whitepapers and websites advocating different approaches to identifying these ‘vital few’ with as many techniques recommended for retaining and developing such individuals.

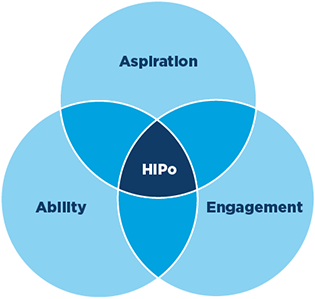

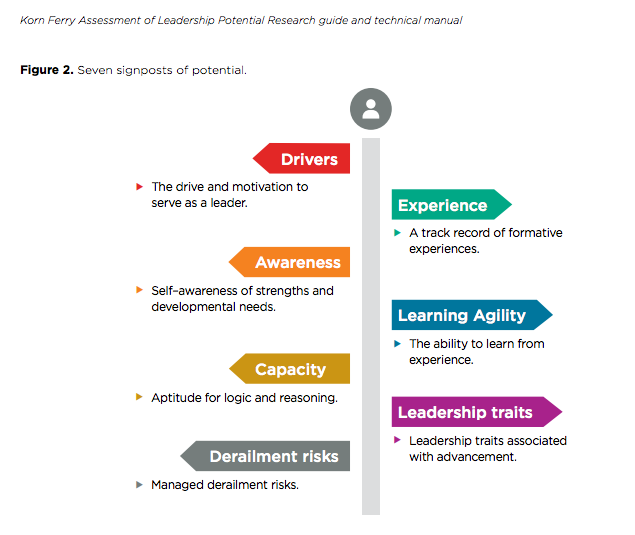

Various consulting firms also have their own models of potential that are widely used:

Given the importance that many organisations place on identifying high-potentials and the vast differences in approaches taken, it seemed a worthwhile exercise to look at current practices and see whether there is any best practice we can learn from.

We put together an online survey covering areas such as how organisations define potential, tools and models they use to identify those that meet the criteria and how they are developed. Some of the questions asked were the same as those used in other similar surveys in the past to allow us to compare and contrast, as well as see if there has been any innovations or improvements in recent years.

Key Findings

- On average, high-potential employees are only identified accurately 45% of the time which suggests either organisations need to find much better ways of doing so or should abandon trying altogether.

- Organisations that report higher levels of success use specific, tailored tools and processes suited to their own unique circumstances. There is no ‘silver bullet’ that will work for all organisations in all contexts.

- Advocates of simplistic models of potential with fewer criteria report stronger engagement and use by Line Managers but these are often less effective in identifying future leaders in the long-term. More in-depth approaches are needed, supported by better training for line managers.

- For organisations operating in dynamic, fast-pace and disrupted industries, a short-term approach is more effective with a focus on individuals’ readiness for their next move. In very stable, slower moving sectors, if they exist, a longer-term approach to identify future leaders in 5+ years’ time may be more worthwhile.

- The further out organisations try to identify future leaders, the more difficult and less successful the process becomes. Those firms with higher levels of success building future leaders are supporting the growth of individuals in their current role and towards the next. Organisations trying to identify individuals with the potential to move into roles at 2+ levels above their current level report a significantly lower success rate.

- Identifying individuals that are ready now or soon will be for specific roles, where the requirements are much clearer than a vague definition of long-term potential is much easier and success rates in more senior positions is much higher.

- 9-box talent grids are still widely used and have their place but should be used to facilitate conversations about talent and not become the end goal of the process. Other models used are variations of the talent grid, typically using 3 or 4 boxes to categorise people.

- Whilst HR or Talent leaders should facilitate the high-potential process, it must be owned and supported by the senior leadership team. Line Managers are then accountable for identifying and supporting the development of their team members that have the potential to grow.

- Stretch projects / assignments supported by coaching and mentoring are the most commonly used combination of development interventions for high-potentials and likely to yield better results. Formal development / training programmes are least widely used.

- Once individuals are promoted into new roles, only a small number of organisations continue to provide support and development to help them in the transition leading to increased risk of derailing. Newly promoted employees need to be supported, particularly in terms of fostering new and different relationships and should have a clear transition plan in place including a stakeholder map. Coaching and mentoring can play a key role here.

- Few organisations identify key metrics that will measure the success of their high-potential programmes success rates, despite this being critical to help inform future decisions.

Detailed Findings

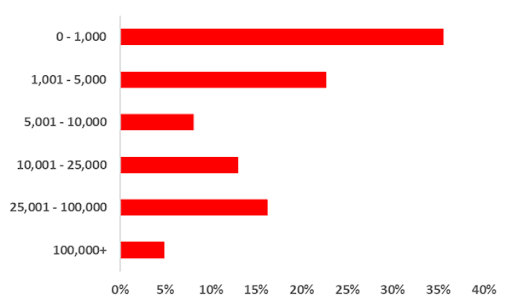

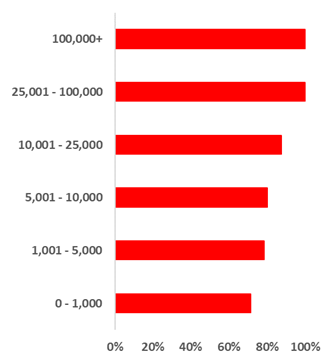

79% of organisations surveyed have an organisation-wide definition of potential with three quarters of those that don’t being in the process of agreeing one. Whilst defining potential is prevalent across all sizes of organisation, there is a noticeable increase in larger organisations as can be seen below:

Potential for what? is a common question when discussing the subject although the vast majority of those we spoke to define it broadly along the lines of potential to move into senior roles at some point in the future, i.e. leadership potential, anything from 18 months to five years with one organisation that looks 10 years ahead.

Those organisations that do not define potential and have no intention of doing so fall into two camps. Either they have tried before and been unable to agree an approach and so have given up, or they do not believe in the value of doing so – as some of our respondents said, “the idea that we are going to bet on these people (high potentials) over the next five years is just a nonsense”; “high-potentials will show themselves anyway so why have a programme” and “focusing attention on less than 10% of the organisation at the expense of the other 90% doesn’t fit with being an inclusive organisation”.

61% of organisations surveyed that have a definition of potential and look to identify high-potentials use a 9-box grid with various labels used for individuals in each box. Developed in the 1970’s by McKinsey and whilst often maligned, it appears to be the most common tool used by organisations today, largely in the absence of anything better.

Critics of the 9-box grid cite a lack of accuracy in assessing potential, completion of the grid becoming the end in itself and the static nature of placing individuals into boxes. However, these are issues with its implementation rather than the tool itself.

Of the third of organisations not using a 9-box grid, we found the majority have developed their own model. However, these models were either variations on the 9-box grid or were not models of potential, rather focusing on readiness as part of succession planning processes.

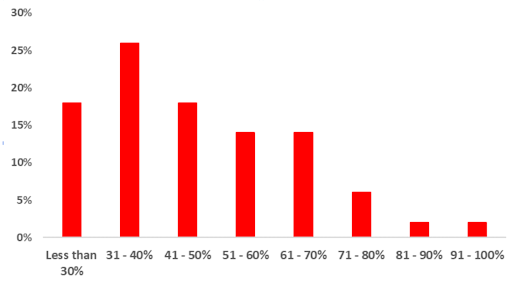

So how successful do organisations feel that they are in identifying high-potentials? We found a staggeringly low success rate of 45%, meaning of those individuals flagged as high-potential, less than half prove to be successful in more senior positions in the future.

The above results suggest that current practices are no more successful than flipping a coin. The consequences of this are significant resulting in many individuals being developed towards and placed into roles they are not suited for, and in some cases roles they do not even want. This not only sets them up for ultimate failure, impacting upon them personally, but there is a large knock on effect for the organisation. This is results in essentially mis-hiring which carries costs of anything from four to 15 times base salary for the organisation.

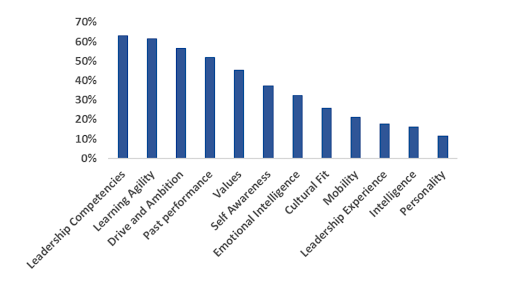

Our hypothesis prior to this survey is that the reason for such a low success rate is due to organisations using the wrong criteria for identifying potential. We looked at many published models of potential, selecting as many different criteria we could find and presented these to our survey respondents to ask which they use:

By comparing the criteria used by those organisations that report higher levels of success in identifying high-potentials to those that are less successful, we found no significant correlation between success and any of the individual criteria used with only a slight uplift in the use of Values and Emotional Intelligence. However, we did find a small link between the number of criteria used within their model of potential with the more successful organisations using a higher number. This could suggest that the more criteria used, the more successful the identification process is likely to be.

From the interviews we conducted with those organisations that do not use a formal high-potential identification process, the above is largely the reason for not doing so. It is not that they do not value having different criteria to help inform decisions on who has potential, but there are so many different aspects to the definition of potential that it becomes too complicated and unwieldy.

A key topic of conversation in our interviews was the specifics of how organisations identify high-potentials and there were two schools of thought:

- An annual talent review process culminating in meetings to discuss and agree placings on a 9-box talent grid. Many of these also include discussions on development for high-potentials and align it to succession planning.

- It is an ongoing process and forms part of all managers roles to develop everyone in their teams, whether they are identified as high-potentials or otherwise, with development needs identified for each specific team member. High-potentials are often flagged on a HR system for succession planning purposes.

Those following the latter approach, were often critical of the static nature of the traditional talent review process, often compounded by a view that potential is fixed for ever. This view is summed up by Scott McNair, Senior Manager – Leadership and Talent at Virgin Money UK, “In physics you’ve got two forms of energy, potential and kinetic. A stretched rubber band is full of potential energy – it’s all pent up and tense. Kinetic energy is released when you let the tension go – things happen. Talent for me is all about kinetic energy, creating useful, constructive movement for people and benefit for the organisation. Too much of our time spent on talent seems to create a potential energy situation – a kind of static-ness which is the opposite of what I think we are trying to achieve.”

Leaders also report “levels of retention of high-potentials is generally quite low” and “High-potentials will not wait for internal high-potential process to help / promote them, they will go elsewhere and get it now” and so an ongoing dialogue is needed and not just a once a year process or meeting led by and often perceived to be owned by HR.

This raises an important consideration which is the mechanism and structures organisations use to facilitate the moves into new roles once high-potentials have been identified by whatever means. Identifying individuals that are either ready for a new position or have the potential to be at some point in the future should feed into succession planning and more broadly as part of the organisations resource management strategy. Although this study has not explored how high-potential employees are moved into new roles, it is clear that organisations need to look at how they create opportunities for their high-potentials in an active way and beyond waiting for opportunities to arise through natural attrition. One HR Director we spoke to reported that circa. 35% of their employees are in middle management positions and whilst the majority of these will not be considered as high-potentials, many are now stuck in their role as there is little room for further career progression. Some of this can be alleviated as the organisation grows and new roles are created, but there is a need for more creative ways to create new opportunities.

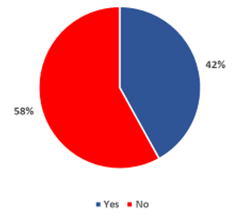

To support or validate high-potential decisions, some organisations, 42% of them according to our findings, use a formal assessment process to evaluate individual’s potential. When we then compare the responses from organisations that feel they are successful in identifying high-potentials compared to those that are not, we see no difference in the use of assessment. However, this is to be expected to some degree given that there is so much variation in how potential is defined, the best assessment process in the world will be ineffective if it is not measuring the right things.

There are two key issues most of our interviewees had with this approach:

- To conduct assessments on everyone in the organisation is expensive, disruptive and complicated

- Assessment becomes a crutch that managers rely upon to make decisions they should be making.

Whilst there was broad agreement that formal assessments including psychometric tools can be useful to help assess potential, it was largely felt that this approach should be used sparingly, mostly to help individuals identify their areas for development and in some case, ‘validate’ their potential. Using external assessment or psychometric tools is not the answer to identify high-potentials.

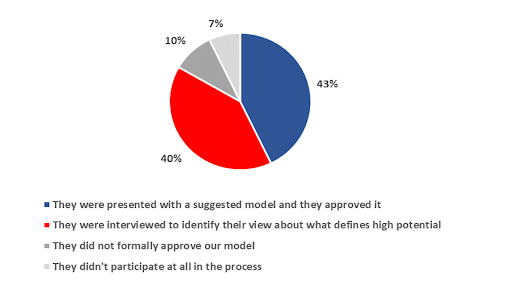

A strong message from the vast majority of organisations is the importance of having the senior leadership team engaged in the process with comments such as “the senior leadership team have to be role models and take the process seriously or no one else will” and “The Executive team need to be involved, have to buy into it, have to own it”. As can be seen from the chart below, in most cases they were either interviewed to get their input into defining potential or approved the model that was developed, typically via HR or Talent teams.

However, whilst senior leadership engagement is clearly important, are they any better equipped to understand potential than anyone else? As one of our interviewees told us, many senior executives have been the beneficiaries of ‘traditional’ approaches to talent management and high-potential identification such as 9-box grids and talent reviews, and so are more likely to prefer similar approaches now, essentially a ‘it was good enough for me so it’s good enough for them’ attitude. It is no wonder therefore that those HR professionals that do not currently have a clear high-potential process in place have tried and failed in the past. They believe that old processes are ineffective but struggle to either identify or get the buy-in of the senior leadership team to different approaches, so they give up.

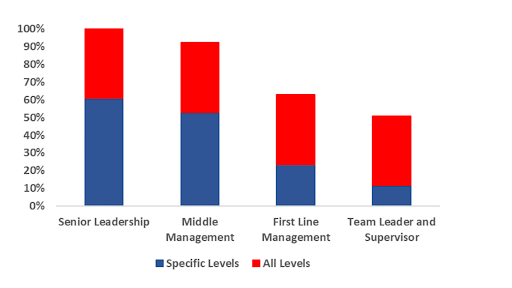

As we expected, more organisations focus their attention on identifying high-potentials at the mid to senior end of the hierarchy although 39% of respondents seek to identify them at all levels of the organisation, with some only looking for high-potentials at more junior levels.

Whilst there is a strong recognition that high-potentials exist at all levels of the organisation, organisations that tend to have formal, HR-led talent review processes are less likely to try and identify them at junior levels. Based on the conversations we had with HR and Talent Leaders, the reason not all organisations look for high-potentials at lower levels is largely due to the impracticality of doing so amongst a much larger population, as well as it being seen as less important to do so by some.

We also found that the lines between readiness and potential are becoming blurred. If potential is about future capacity to perform in a more challenging or senior role then readiness is concerning preparedness in the short-term for a specific role. High-potentials have the future capacity to develop the capabilities and acquire the experience needed at a more senior level, whereas those individuals that are ready now generally already have them or at least the majority.

It was clear during our discussions with HR and Talent leaders that there is significant overlap between readiness and potential with many seeing them “as part of the same thing”. However, in a number of organisations, particularly those within sectors that experience significant disruption and change, there seems to be a shorter-term focus when it comes to talent in general. In sectors such as technology, digital, media and some sub-sectors of manufacturing that tend to be faster moving, our interviews suggested a move away from a long-term, 9-box grid approach to identify high-potentials to a focus on short-term readiness to move to bigger or broader roles and not necessarily more senior one. As one respondent commented, “Formal high-potential programmes are much more challenging in fast moving organisations and sectors such as ours” largely due to the pace of change meaning that their business strategy is more fluid and so identifying the types of leader they need in the medium to long-term is much more difficult to predict.

We were also keen to understand the different approaches organisations take to the development of their high-potential pools:

When we compare the data from those organisations that see a better success rate with identifying high-potentials with those that are less successful, there was only one key difference – They use a wider blend of interventions on average as part of their high-potential development (5.8) than their less successful counterparts (4.1). No one intervention was found to be used more or less frequently by either group, although the use of stretch projects supported by coaching & mentoring is the most common combination.

Other advice and comments we received through our interviews include:

- “Appoint a buddy for each high-potential, someone that will sponsor them”

- “Career development” – who knows what skills we might need in the future. Focus on helping individuals build their careers”

- “Careers are not built by constant upward steps. High-potentials understand they need to learn to grow not just to progress”

We found that the vast majority of organisations provide various development support to help high-potential employees develop the capabilities required in more senior positions. However, there seems to be a drop off in support once they have been moved into new roles. As one of our interviewee’s told us, “the skills needed to get to a leadership position are different to those needed in a leadership position”.

Particularly during the transition into a new role, the risk of derailment is significant as newly promoted individuals struggle to adapt and form the new relationships they need to be successful. As they move into a more senior position, their teams, peer groups and other internal and external stakeholders’ change and need to be managed in order to get the support required, in the same way a new hire has to build relationships. However, this is often neglected for internally promoted employees as it is often assumed relationships are already in place but even where they exist, the dynamics will be different and need careful planning and ongoing management.

The final area we investigated was whether organisations were transparent with employees about the fact that they have a high-potential programme.

We found that 60% of organisations are open about where individuals sit in terms of their potential and received comments from “transparency is key” and the process should facilitate “open and candid discussions” through to “High-potential programmes and succession plans can be divisive” and “Telling high-potentials that they have been identified as such creates a sense of entitlement or expectation that the organisation cannot fulfil”.

Contact:

Email: paul.surridge@targetleadership.co.uk

Telephone: +44 (0)7587 003990

www.targetleadership.co.uk